Abram Lincoln Articles

Article Page Contents:

The Name Is Abram; a few notes on Abram "Abe" Lincoln - by Shirley Klett

by Floyd Levin This article appeared in the November 1999 issue of Jazz Journal

International and is reproduced here with the author's permission. Reviews following the event praised Hackett's combo and especially lauded the tall handsome trombonist. The Dixieland Jubilee concert was a "warm-up" for the Hackett group's memorable record date that followed. A few days later, the same band, with Jack Teagarden added, recorded ten tunes for Capitol Records. Hackett's lovely tone was then enhancing several Jackie Gleason albums of mood music, but he had retained his hot jazz skills. When released, the album, Coast Concert, presented an informal Dixieland sound reflecting the happy rapport among the players and showcasing the pair of world class jazz trombonists sharing the solos. It is still considered one of his best sessions of the decade. "Teagarden and I were havin' a ball working together," Abe told Bill Spilka in a 1978 interview. "During the recording date, there was never a feeling of competition. I realize that nobody can play like Jack - but I always had a flashy spirited style of my own! So we got along just great!" When asked how it was to record with Abe Lincoln, Teagarden replied, "Fine! I just got out of the way when it was Abe's turn!" Abram (Abe) Lincoln was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania on March 29, 1907. "A lot of good musicians came from that coal mine area," he said during Spilka's interview. "The Dorsey Brothers, Fuzzy Farrar, Russ Morgan, the Waring Brothers, etc. There was a good little college group called the Maple Leaf Orchestra. "My Dad, John Lincoln, played cornet in the Lancaster City Band and the Iroquois Band. He would take me with him when I was a youngster and sat me behind the trombone players so I could follow the music over their shoulders." Abe always spoke reverently about his father, although he was a strict taskmaster. "He taught my brothers and me how to play our instruments. He was proud of us, I'm sure, but he never gave us credit. No matter how well we played, he'd say, 'You could have played it better!' He was right. That made us pay attention to what we were doing. Any smart teacher will do this. Music is one study that never ends - so you can't get too good! Just play. Let the audience decide how good you are. That was my Dad's philosophy - and it worked! "I only had a grade school education - I was more interested in playing the horn than going to school. I spent my whole life playing. I started to make money on the horn when I was six or seven years old. I played a solo on the peck horn in my hometown on New Years day. I got five dollars for first prize. "I had five brothers - three were musicians. Bud and Roy played trumpet, and Chet played trombone. My brother Bud would have been right up at the top of the trumpeter's [list] if he hadn't had a fatal accident. He was on a par with Phil Napoleon, leader of the Original Memphis Five, then the leading white jazz group in the country." Bud Lincoln formed a six piece band in 1921. He played trumpet and Abe was the fourteen year old trombonist. They took almost any job offered to them - strawberry festivals, dances, parties, picnics, college proms, etc. "Bud was six years older than me. He went to the dances, heard all the bands and brought the tunes home for me to learn. After we learned a lot of songs, I began improvising. You know, I could take a tune and 'noodle' around with it without the music - spontaneously. I'm not bragging, but it did come naturally. Bud Lincoln and his Jazz Band broke attendance records at the local Bach Dance Auditorium and also played a summertime engagement at the Rocky Glen Park in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Abe remembers two recording dates with his brother's band for the Edison and Victor labels. The Edison records were rejected, and Victor decided not to release the Lincoln records because the company had a contract with the Original Memphis Five and "did not have room for another jazz band." (Miff Mole, the OM5's esteemed trombonist was one of Abe's earliest influences.) Abe's first issued recordings were with Ace Brigode and his Fourteen Virginians on the Okeh label in 1924. "Ace approached my father to let me go to New York with his band when I was about 16 years old. He had a hotel band - a good band to dance to. It was a corny band, but I didn't care, I was getting paid!"

Recalling one of the first Brigode record sessions in New York City on October 13, 1924, he said, "It was Alabamy Bound. I think I played a sixteen bar solo or a chorus. At that time, we had no microphones - we blew into those large conical horns. It was a 78 RPM Columbia, but I never heard the record." "I made a study of 'false positions.' People say, 'You don't move the slide very much.' I tell them, 'You don't have to move it very much - the notes are in there if you know where they are!' I used to play a jazz chorus with a piece of hotel stationary over the bell - the thin paper vibrated and sounded like a kazoo." A discographical exploration of Abe Lincoln's recording activities underscores the importance of his role in the jazz scene. Since those early sessions with Ace Brigode in 1924-25, his shellac and vinyl trail covers a broad spectrum of the music. When Abe left Brigode in February 1925, he joined James B. Dimick's Million Dollar Sunny Brook Orchestra and went to Detroit to play at the Arcadia Dance Hall and the Hollywood Theater. After the dates with Dimick's Orchestra, Abe returned to New York. When he joined the popular California Ramblers in New York 1926, the adolescent recording industry was paralleling the public' s increasing interest in a new exciting music and the Rambler s provided many recording opportunities for Abe. His powerfully humorous touches on their recordings influenced several generations of jazz trombonists; that influence continues to this day. "We were under contract to Columbia Records," he told me when we chatted during his 90th birthday party at his home in Van Nuys, California. "That didn't prevent us from recording for other labels using different names. For Pathe' Actuelle, we were the 'Palace Garden Orchestra.' On Perfect, we were billed as 'Meyer's Dance Band.' Grafton Records called us the 'Windsor Orchestra'." Abe said that the Ramblers' various groups made more records than any band in New York. During the month of April 1926, they recorded over a dozen tunes using several pseudonyms on ten different labels. The California Ramblers were in a recording studio almost weekly. Using numerous band names, their records appeared on most of the independent labels active in the mid-'20s including: Edison, Harmony, Silvertone, Pennington, and Broadway. "I made quite a few records with the California Ramblers - I never heard them afterwards. We were one of the first bands to record with a microphone. I think it was I'd Climb the Highest Mountain for Columbia Records at a Columbus Circle studio in Manhattan. After listening to a playback, we all said, 'What a difference!' It was much easier on the guys making the records. It meant more relaxation, less nervousness, etc.

Despite their name, the California Ramblers were not from the West Coast and never played there. The Ohio group was formed by banjoist Ray Kitchenman in 1921, and named after their early venue, the Ramblers Inn on Pelham Parkway, Bronx, New York. Violinist Arthur Hand was the leader. Ed Kirkeby, the group's manager/agent had extraordinary marketing skills and soon secured bookings for them in prestigious venues. A decade later he masterminded Fats Waller's career. The importance of the California Ramblers in jazz's history has been overshadowed by their reputation as a dance band. They were far ahead of contemporaries who retained a tense rhythmic and melodic rigidity. Unlike the other leading dance bands of the '20s, led by Roger Wolfe Kahn, Ray Miller, Isham Jones, and Paul Whiteman, the Ramblers featured a buoyant rhythm section sparked by drummer Stan King. Their exhuberant music anticipated the oncoming Swing Era, and was often based on stock arrangements cleverly modified to feature hot solos by the best jazz men in N.Y. An integration milestone occurred when cornetist Bill Moore joined the band; he became the first regular black member of a white orchestra. Over the years, the California Ramblers' personnel included, at various times, the top rated instrumentalists of the day, including: Spiegle Willcox, Chelsea Qualey, the Dorsey Brothers, Fud Livingston, Red Nichols, Phil Napoleon, Miff Mole, and Adrian Rollini. During this period, Rollini, a master bass saxophonist, extended its role as merely a rhythmic "ump-pa-ump-pa" cadence device and transformed the ungainly horn into a viable solo instrument. He fronted some of the Rambler's smaller groups like the "Goofus Five" (Rollini was probably the only musician who played the the "Goofus" on recordings. It was a toy-like novelty instrument, actually a keyboard harmonica.)

"This was about the time I met Tommy Dorsey," Abe told Bill Spilka during an interview in 1978. "He used to ask me how I'd do things - how I played things [on the horn]. He'd say, 'How do you do this?' "I'm talking about Tommy Dorsey! I said cheeze! I think he was the finest trombonist that ever lived. The way he handled his breathing, and everything he did. Tommy was a perfectionist - and he's asking me these questions! I said, 'I don't know how to tell you, Tom. You'll get that feeling - and that's it!' That's all I could tell him! "I left the Ramblers when I got a call from Detroit to join Sammy Dibert's band. Sammy played reeds and his brother John played banjo. They both came from Lancaster and worked in my brother Bud's band with me." While in Detroit, Abe sat in with the Goldkette orchestras, worked in the Michigan Theater Orchestra conducted by Ed Werner, and recorded Rossini's William Tell Overture. The record was later used as the radio theme song for the Lone Ranger when the program was launched in Detroit in 1930. "Can you imagine how many times that record was played?," he recalled. "The program was heard 52 times a year for over two decades. Too bad we were not paid residuals in those days!"

After the Detroit jobs, I went back to Lancaster to organize my own orchestra." The orchestra included his three brothers, Bud, Roy, and Chet, in the brass section. "We had nine pieces, did our own arrangements, things like Washington and Lee Swing. We sounded pretty good playing around town." The Abe Lincoln Orchestra played at the Valencia Ballroom on the pier in York, Pennsylvania during October 1933. Apparently they made no recordings. "It was a good band, but it broke up when I went back to New York." In the '30s, Abe worked with bands led by Roger Wolfe Kahn, Leo Reisman, Paul Whiteman, and Ozzie Nelson. He left New York with Nelson's orchestra when they came to California to appear on the Joe Penner radio program. When Nelson returned to the East in 1936, Abe remained in Los Angeles and soon joined the ranks of the busy radio studio musicians working with John Scott Trotter (Kraft Music Hall), Billy Mills (Fibber McGee and Molly), Victor Young (Al Jolson Show), Johnny Green (Packard Show with Fred Astaire), Freddy Rich (Abbott & Costello Show), etc. "In those days, the studio orchestras were signed up for 26 weeks. I paid no attention to who the star was. I just played the music. It's a business - a livelihood. I played first chair trombone in radio studios for 25 years."

Abe gracefully side-steps questions regarding his unique name and an apocryphal tale that has been told and re-told by musicians and fans over the years. The often repeated episode is probably the best "musician's story" in jazz history. Numerous variations have perpetuated the legendary saga which Abe vehemently denies actually occurred. The story, apparently only partially based on a factual incident, is so appropriate, it should be included here. This is one of the many versions: It seems that Abe and another noted trombonist were stopped for a traffic violation while driving home together after a job. The police officer grimly asked Abe, the driver, "What's your name?" He replied, "I'm Abe Lincoln." The officer, obviously annoyed, said, "O.K. Wise guy! I guess your buddy there is George Washington!" Abe answered, "As a matter of fact, he is -this is George Washington!" His companion was a highly respected former member of orchestras led by Don Redman, Benny Carter, Fletcher Henderson, and Louis Armstrong. George Washington was his legal name. ************************************ The following article is reproduced from the July 1989 (volume 22, No.3) issue of the IAJRC Journal, published by the International Association of Jazz Record Collectors. The webmaster would like to extend his heartfelt thanks to the officers of IAJRC for granting permission to include this article. THE NAME IS ABRAM A FEW NOTES ON ABRAM “ABE” LINCOLN By Shirley Klett (author's note: I had the pleasure of spending the afternoon and evening with trombonist Abe Lincoln, his son, and his daughter, following the IAJRC Convention in Los Angeles (August, 1987). This was a purely social occasion, but I naturally "got what I could" out of my host. I made some notes on our conversation concerning his early years in music and, eventually, got them written up. To clarify some points, I asked Abe's daughter, Joyce, to have Abe verify the names of bands, venues, etc., in my rough draft. The information Joyce relayed from Abe contained further information. As I have not talked personally with Abe on these further facts, I have labeled them as "notes." However, since virtually nothing has been published about Abe Lincoln, rather than delay it until I could go over matters with him personally, I've put everything together in what seems to be a logical sequence and added comments, where appropriate. I hope to arrange another visit with him to go over his career in more detail and would welcome suggestions, ideas, and questions from members.) According to the discographies, the bold, brash trombone of Abe Lincoln first got on record in mid-October of 1924 when Ace Brigode and his Fourteen Virginians re" corded for Okeh in New York City. The titles were "Bye Bye Baby" and "A Sun-Kist Cottage in California." Abe reports his first recorded solo was" Alabamy Bound" and came on the succeeding Brigode session of January 13, 1925 (Columbia 282-D backed by, again, "Sun-Kist ... "). Ace Brigode had approached Abe's father about hiring Abe to play with the 14 Virginians when Abe was 14 or 15 (1921-1922) (Abe had begun on trombone at 5 and was soon playing in bands with his father and with brother Bud, who played trumpet). His father was so delighted with his regular job with Brigode that he firmly counseled Abe not to accept offers he got from leaders like Sam Lanin and Roger Wolfe Kahn. Nevertheless, lured by a higher salary, young Abram left Brigode at the end of January or in early February, 1925 for James B. Dimick's Million Dollar Sunny Brook Orchestra in Greensville, PA. He was replaced by trombonist AI Delaney and is not on further Brigode sessions after the" Alabamy Bound" date. The Dimick Orchestra traveled to Detroit to play the Arcadia Dance Hall and opened the Hollywood Theatre in Detroit with Richie Craig as the M.C. Note: Abe spent some, time in Detroit playing at the Arcadia, sitting in with the Goldkette bands, and then was with Ed Werner at the Michigan where Lou Kosloff guest conducted. He then returned to New York to join the California Ramblers to open the Hippodrome. Note: I had asked Joyce to check the name of the orchestra which opened the Hippodrome and the reply was that "The Ramblers opened the Hippodrome (7922-7923) with 'Sand.’ Abe may have intended "San" and this will have to be checked, but, asked a question out of context, he has placed the year too early. The Hippodrome was first opened in 1905 and was a huge venue at which some of the most lavish productions were staged. As the mid-twenties approached, the Hippodrome was having difficulty financially and so closed down for refurbishing and "opened" in 1925 as a vaudeville theater. This may have been the opening Abe recalls - or he could be referring to the Rambler's opening, of course. Whenever it took place, the event sticks in Abe's mind because a group of midgets lived under the stage (they charged 25 cents a tour) and the small "city" they'd fashioned there, complete with fire department and other amenities, fascinated him. Abe seems to have stayed around New York for a couple of years as recording sessions with various California Ramblers' groups took place quite regularly from late July, 1925 through fall, 1927. Note: In the material Joyce typed up for me, Abe states that he recorded "In 7923 with California Ramblers for Harmony and Cameo Records, a few Columbia's and Okeh under owners'/leaders' Arthur Hand and Ed Kirkeby. Some titles were: Sister Kate, Ace in the Hole, Beale Street Blues plus others. "This statement came in connection with the question about "opening the Hippodrome" so the year 7 923 follows naturally from the year he assigned to the Hippodrome experience. While in New York with Ace Brigode he could very well have recorded with the Ramblers in 7923, although the titles he specifically remembers recording were among those done in University Six sessions in 7926 and 7927. Keen Abe Lincoln fans will note that Abe is not listed as present on those titles in the standard discographies but current discographical research as listed on the English Harlequin series of University 6 LPs, show him as the trombone on the sides he recalls. Abe then played with his brother Bud Lincoln's Jazz Band (based in home town Lancaster, PA) and with the Brunswick 7 (another Lancaster unit). He recalls one recording session for Victor with Bud's group (February 13, 1926) but it wasn't issued because the Memphis 5 were under contract with Victor and "there wasn't room for another jazz band." Cork O'Keefe was the booking agent for Bud's band (this is the 0'Keefe of the Rockwell-O' Keefe booking agency, formed in 1927) and the group broke attendance records at the local Bach Dance Auditorium. They also played Rocky Glen Park (Scranton) in the summertime with Franky Deal (proprietor of the dance hall). One date was a Phi Kappa Sigma dance at Continental Hall in Philadelphia which was such success that the Lincoln band was solidly booked from that time on. He met Russ Morgan and Jimmy Dorsey as they came thru Lancaster with the Scranton Sirens under Billy Lustig. Note: The comment about the Scranton Sirens obviously applies to earlier years. Abe reports the personnel for the Victor recording session as Bud on trumpet, himself, Sammy Dibert (sax), Frank Whitman (kyb), John "Fat" Dibert (gtr, bjo), and "Chief" Jamison (tuba). Note: One title from the rejected Edison session of October, 7925 has been issued in Neovox cassette # 77 4. I sent it to him at the time and he denied it was Bud's group. This needs further exploration. Abe is sure his brother Bud would have been right up at the top of trumpeters if he hadn't had a fatal accident. Abe married in 1929, just before his 21st birthday. The need for a stable income was now of primary importance to him. He played the Reisman radio programs (1931-1932), the Phillip Morris show (Reisman also conducted for this, 1933), and did the last George Gershwin tour under Charles Previn, who never used a baton to conduct (c. 1933). While in New York with Reisman, Abe was approached by Benny Goodman about joining a band he was forming. Benny told Abe, "stick around, I may have something for you" but nothing ever materialized. Abe joined Ozzie Nelson in 1935 and touring with Nelson brought Abe to ((the coast" (1936), where he decided to stay and strike out on his own. During the first year there he could just play "casuals" while waiting out the transfer to the Los Angeles union. One such casual was with Smith Ballew at the Club de Paris in Hollywood. Abe was finding it tough to get started in L.A. until one night Cliff Webster and Charlie Green came in and requested Tiger Rag ... Webster and Green were so impressed that they spread the word and Abe suddenly found himself in great demand. After that, he never lacked for work. Between about 1942 and 1947, he is on many sound tracks of Buster Keaton cartoons. He played for John Scott Trotter for years and backed, among others, Bing Crosby and Dinah Shore. On the side, though, he and some like-minded partners opened a night club called "Open House" at the corner of LaBrea and Melrose-Abe employed pianist Bob Zurke at $125 per week. Abe says the night club was great but the headaches involved in managing it were just too much so he eventually sold out his share. Abe always retained his interest in jazz and took his opportunities whenever he could find them. Consequently, you will find him blowing the lusty trombone on many of the Matty Matlock led Rampart Street Paraders recordings and he is on a number of other recording sessions made in "Hollywood" including sessions with Bob Scobey, Pete Fountain, and Ray Anthony. He also made a Paul Whiteman tour. The most renowned of his later jazz sessions, though, is the Hackett session for Capitol with both Jack Teagarden and Abe Lincoln entitled "Coast Concert." Jack is reputed to have replied, when asked how it was working with Abe, ((Fine. I just get out of the way when it's Abe's turn." My favorite story about this LP is that a friend who was a dedicated and expert jazz collector once wrote to me concerning it, “lt's too bad they didn't let Lincoln solo on it" when, in fact, Abe and Jack split the trombone solo space evenly! I should talk. The fact is, some years ago when my husband and I were asked if we'd ever heard of a trombonist by the name of Abe Lincoln there was a profound silence from both of us and finally Jim said, Well, I've heard of George Washington." There are numerous Lincoln stories. Abe moonlighted with Wild Bill Davison at the Huddle in West Covina. Abe lived in Santa Monica and Bill in another part of the Los Angeles sprawl. One night Bill got home, went to bed, and was awakened in the small hours by the telephone. It was Abe and he demanded with great urgency that Bill get over to his place immediately. In great alarm, Bill threw on some clothes and drove furiously to the Lincoln residence. It turned out that Abe had solved the problem of keeping a keg of beer “on ice" by drilling a hole through the side of a refrigerator in order to have the tap on the outside and it was now possible to have cold “draft beer" on hand continuously. Despite the admiration for Abe's trombone among musicians, he has remained pretty much an underground cult among jazz collectors, and this may be as much Abe's fault as ours. I was somewhat astonished when virtually the first thing he wanted me to know was that his name was “Abram," not “Abraham." He was immensely pleased that John Chilton had put him into “Who's Who In Jazz" but was somewhat annoyed that he hadn't gotten the name right. He admitted to receiving a questionnaire to be filled out for it, but had thrown it away! Fans who managed to find an address and sent him notes of appreciation received no reply: Nevertheless, Abe is able to produce examples of fan mail at a moment's notice so their letters have been treasured. As for interviews-he feels most would-be interviewers aren't interested in him, but want to know about more famous musicians he's known and worked with. His attitude to fans is that he loves them, but at a distance: He feels that if you start answering your mail you'll be pestered and soon have no time for yourself. Now, there's a good deal of truth to Abe's beliefs on these issues. On the other hand, he's kept himself so private that a number of well informed collectors were astonished to hear I'd gone to visit Abe Lincoln - they could have sworn he died years ago. Abe retired from the studios almost seven years ago. He had, shortly before my visit, played a wedding after a five year layoff. He hired “the best" for it, he said, commenting about Peanuts Hucko that he admired him greatly because he had never stopped listening and developing. Concerning the wedding, he reported that he was bad through the first set, but had gotten the old lip working well by the second. I can attest to his vim and vigor, his excellent memory, and the skill with which he barbecue steaks. Trombonist Abe Lincoln, at 92, is among the few living jazz greats whose extended careers thrived during the Jazz Age, the Swing Era, the Dixieland Revival, and continued almost to the present. Lincoln is also a member of a select group of influential artists who are highly admired by fellow musicians but have eluded the attention of the average jazz fan. His name appears only briefly in most source material usually in reference to his activities as a sideman with noted leaders. Few publications have printed major articles depicting his elaborate career.

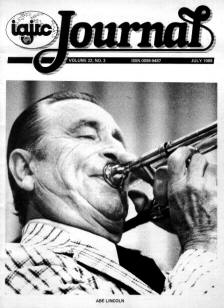

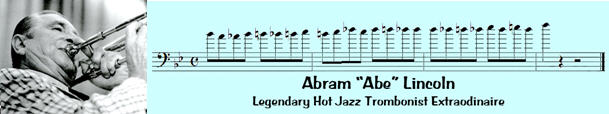

Trombonist Abe Lincoln, at 92, is among the few living jazz greats whose extended careers thrived during the Jazz Age, the Swing Era, the Dixieland Revival, and continued almost to the present. Lincoln is also a member of a select group of influential artists who are highly admired by fellow musicians but have eluded the attention of the average jazz fan. His name appears only briefly in most source material usually in reference to his activities as a sideman with noted leaders. Few publications have printed major articles depicting his elaborate career.

This profile is intended to rectify that unfortunate oversight. I clearly recall the first time I heard him. It was October 15, 1955 on the huge stage of Los Angeles' Shrine Auditorium during Frank Bull and Gene Norman's Eighth Annual Dixieland Jubilee. Cornetist Bobby Hackett, making a rare West Coast appearance, fronted an all star-band. I marveled at the robust sounds created by the tall handsome trombonist. A glance at the program identified him as Abe Lincoln. The band also included: Matty Matlock, clarinet, Nappy Lamare, guitar, Don Owens, piano, Phil Stephens, bass, and Nick Fatool, drums.

His trombone is heard on recordings with Bing Crosby (1937, 1941), Hoagy Carmichael and Pinky Tomlin (1938), and Judy Garland (1939). The Carmichael recordings, featuring Abe in Perry Botkin's Orchestra accompanying the composer, included Carmichael's successful Hong Kong Blues and Riverboat Shuffle. Lincoln's horn was also an important voice in several Walter Lantz Woody Woodpecker cartoons and Buster Keaton comedies. He could bray like an elephant and create humorous animal sounds to merge with the action on the screen.

When Dixieland music was resurrected during the '40s, Abe returned to jazz and recorded with Wingy Manone, "Wild Bill" Davison, Pete Fountain, Bob Scobey, Matty Matlock, and Red Nichols. It is interesting to note that he played and recorded with Red Nichols in New York City in 1925 at the peak of the Jazz Era, and three decades later, resumed his association with Nichols in Los Angeles adding impetus in the surging Traditional Jazz Revival movement that is still in progress.

The 1956 Nichols/Lincoln recording reunion re-created several numbers they introduced in the '20s. Abe's recordings with Bob Scobey's Frisco Jazz Band, the Jack Webb-Pete Kelly Big Seven, and Pete Fountain's Dixieland All Stars provided further steam to the Dixieland renaissance. The City of New Orleans, recognizing Abe's important recording activities, presented him with a gold key to the city. His trombone artistry was prominently featured on TV when the Matty Matlock's Rampart Street Paraders appeared on the acclaimed Stars of Jazz telecast on July 30, 1956. Down Beat Magazine's Readers' Poll on August 22, 1957 was a tribute to Abe's enduring style. Amid the subscribers' overwhelming attention to the "modernists," Abe was respectfully eighth in the trombone division behind J.J. Johnson, Bob Brookmeyer, and Bill Harris - and ahead of Urbie Green, Lawrence Brown, Trummy Young, and Kai Winding. He was also honored by Playboy Magazine's All Star Jazz Poll in 1958 and 1959.

From 1953-60, Matty Matlock's Paducah Patrol and his Rampart Street Paraders recorded scores of tunes for Warner Brothers and Columbia Records using the finest Dixieland players including Abe Lincoln, Clyde Hurley, John Best, Eddie Miller, George Van Eps, Stan Wrightsman, Morty Corb, and Nick Fatool. Matlock's fine arrangements in the Bob Crosby tradition allowed ample space of Abe's mighty trombone slurs and slides. After a hiatus of several years, he surfaced with "Wild Bill" Davison's band at the ill-fated "Championship of Jazz" that began August 1, 1975 in Indianapolis, Indiana. During one set, while the band was plying All of Me, Davison, who considered Abe one of his favorite trombonists, without warning, pointed to him to sing the chorus. Slightly flustered, Abe forgot some of the lyrics and finished the chorus on his trombone. Davison, looking up to the balcony, told the audience, "Abe was a little unsettled on that tune. He thought he saw John Wilkes Booth up there!"

In 1976, Abe was a featured artist at the Sacramento Dixieland Jubilee. "They asked me to lead a sixteen-piece trombone choir - I guess with every trombonist at the festival. I made the arrangements on the spot - I told them, 'I'll take the intro and play the first chorus - then each of you play a 32 bar solo - we'll harmonize behind you. Then I'll do a few choruses and we'll end with a big chord.' The fans in Sacramento loved it!" Twenty three years later, the 1999 Sacramento festival was the scene of a special Abe Lincoln tribute by trombonists Bill Allred and Mike Pittsley. Lincoln's two ardent admirers played Ida, Sweet As Apple Cider based on his classic recording with Matty Matlock four decades before. Their high octane duet shook the venerable Crest Theater with an effervescent swing.

Twenty three years later, the 1999 Sacramento festival was the scene of a special Abe Lincoln tribute by trombonists Bill Allred and Mike Pittsley. Lincoln's two ardent admirers played Ida, Sweet As Apple Cider based on his classic recording with Matty Matlock four decades before. Their high octane duet shook the venerable Crest Theater with an effervescent swing.

Allred, a disciple of Abe's, leads his Classic Jazz Band from Orlando, Florida playing the same Matty Matlock Paducah Patrol arrangements that established his mentor as a front runner during the revival era. Pittsley, a member of the Jim Cullum Jazz Band, is also greatly influenced by Abe Lincoln. When I asked him to define the Lincoln style, he said, "He is very extroverted - always front and center. He has an immediately identifiable sound. When I play a hot solo, Abe is always in my mind's ear!" The fiery Sacramento tribute was taped by Jim Cullum's Jazz Band from San Antonio, Texas as a segment of their popular P.R.I. (Public Radio International) series, Riverwalk, Live From the Landing.

The officer immediately placed the two musicians under arrest and escorted them to the police station where they were booked for drunk driving. At the station, after presenting their identification, the embarrassed arresting officer apologetically offered the pair a cup of coffee and they were released. "That's old stuff," Abe said."I don't talk about it any more. They've dogged me about that story for years. It never happened!"

He also reluctantly admitted wearing a stove pipe hat and a black morning coat during a recording session with Paul Weston. "The hat didn't fit me," he added, "but Paul wanted a photo for the album cover, so what the hell, I did it!"

A very memorable event occurred on August 2, 1999. A select group of Abe's family and friends gathered in his home to witness an intimate concert/love-in by the Jim Cullum Jazz Band. The famed group, on a three-week West Coast tour, flew from Northern California to pay a special tribute to their ailing inspirational champion. They played for our small gathering with the same verve they would project for a major concert crowd. Abe, seated next to his colleague, drummer Nick Fatool, beamed broadly and enjoyed the sincere tribute. The following morning, the Cullum band flew to Oregon to continue their tour.

This long overdue profile of Abe Lincoln is far from complete. There are many facets of his lengthy career that still require exploration. Hopefully, one day, jazz scholars will uncover those additional facts. Until then, this piece will partially illuminate the significant role he played in the ongoing classic jazz experience.

The above information was assembled from material in this writer's files and conversations with Abe Lincoln. I am also indebted to British trombonist-bandleader Tony Bracegirdle for encouraging this project and to Bill Spilka and Mike Pittsley for generously sharing their unpublished interviews conducted with the trombonist in 1978 and 1995. Shirley Klett's excellent article, "The Name Is Abram," in the Journal of the International Association of Jazz Record Collectors, July 1989, was very helpful. Additional assistance was provided by jazz research specialist Eugene E. Grissom, jazz film archivist Mark Cantor, and Abe Lincoln, Jr.